Sprinting in the sports of athletics is a race over a short distance with a burst of speed at distances ranging from 50m to 400m. Distances up to 200m are considered short sprints while those above 200m till 400m are considered long sprints.

A runner reaches top speed within 45m to 70m and usually maintains his or her top speed for about 10m as top speed cannot be maintained longer than this due to the usage of creatine phosphate stores in muscles. As a matter of fact, the ability to reduce the rate of deceleration after this is what differentiates top sprinters.

The energy currency of the cell during short sprints of up to 10 seconds is generated by creatine phosphate. This serves as a rapidly mobilizable reserve of high-energy phosphates in skeletal muscles.

Having all these at the back of our minds, then the focus of this article will be limited to the 100-metre and 200-metre sprints.

Becoming one of the fastest men or women in the world is all about years of hard training, healthy eating, total sociocultural factors and the choices the athletes have to make. For instance, the Nigerian Olympic gold medalist at the Sydney 2000 summer games, Enefiok Udo-Obong, described his life’s strict regime in Lagos recently, that he never visited a night club until he retired as a professional athlete.

Life sciences have also confirmed that the ability of skeletal muscles to produce force at a high velocity, which is crucial for success in power and sprint performance, is strongly influenced by genetics and 2 a-Actinin-3 (ACTN3) R577X polymorphism has been strongly implicated in this. This gene is favourable for sprinting and is commonly found in athletes of Black African origin, according to research.

Athletes of Black African heritage have been commanding the sprint events at the Olympics and World Athletics Championships ever since American runner Jesse Owens took the 1936 Berlin Olympics by storm. As a matter of fact, the last 25 holders of the world record for the 100-metre race have all been black; and data compiled in 2007 revealed that 494 out of the 500 best-ever 100-metre sprint times are held by athletes primarily of Black African origin.

But biology alone does not explain this because up till this moment, only Frankie Fredericks of Namibia’s 200-metre gold medal at the 1993 World Athletics Championships in Stuttgart has graced the sock drawer of Africa’s athletics, and no African woman has ever won a gold medal at the sprint (100 and 200-metre specifically) at either the Olympics games or World Athletics Championships, which are the two leading international competitions for elite athletes.

So even among the athletes of Black African heritage, ‘geography’ seems to play a part in successes because those from Europe, North America and Caribbean origins are clearly more successful in sprints than those from Africa. So, curiously, if these athletes of Black African heritage are generally so endowed genetically with ACTN-3 (sprint gene), why then have Africans fallen short so consistently at the highest level?.

A fact already established is that technological advances have always improved all sports performances, and the sprints are no exception. Starting blocks, synthetic track material, shoe technology, quality financial supports accompanying proper training partnerships and sponsorships are requisites to tilt the balance of sports’ successes beyond the advantage of genetics.

For instance, the world record in the 100-meter dash in 1924 was 10.4 seconds, while in 1948, (the first use of starting blocks) was 10.2 seconds, and was 10.1 seconds in 1956. The constant drive for faster athletes with better technology has brought man from 10.4 seconds to 9.58 seconds in less than 100 years.

Could all these practices which are evidently far below global standards in Africa be the bane of African athletes?.

There are far too many questions simply begging for answers.

Now, Let us check the history of sprints and the highly elite sprinters in Africa.

Frankie Fredericks (who was a council member in the World Athletics), has broken the 20 seconds barrier for the 200m on 24 occasions. He also holds the joint-third-fastest non-winning time for the 200m. In August 1996, Fredericks ran 19.68 seconds in the Olympic final in Atlanta, Georgia.

He is also the oldest man to have broken 20 seconds for the 200m. On 12 July 2002 in Rome, Fredericks won the 200m in a time of 19.99 seconds at the age of 34 years 283 days. In 1993, in Stuttgart, he became Namibia’s first World Champion, winning the 200m. He is by far the most accomplished male sprinter from the continent of Africa. Despite all these, he was only able to manage to win Africa’s first and sole gold medal at a major championships till date, in the 200m event. He also ran 9.89 seconds to win the silver medal at the Atlanta 1996 Summer Olympics, which was the highest level any male African athlete has attained in that event.

Nigeria-born Francis Obiorah Obikwelu ran 9.86 seconds to win silver medal at 2004 Athens Olympics, but this was accomplished while flying the Portuguese’ flag (Europe’s influence on him?). Thus far, Namibia’s Frankie Frederick’s effort of 1996 in the 100m remains the peak under the flag of an African country.

Olusoji Adetokunbo Fasuba, having beaten Frankie Fredericks’ previous mark also did not attain the pinnacle of the event. Fasuba was the 100m African record holder with 9.85 seconds until Akani Simbine of South Africa broke it with 9.84 seconds in 2021, followed by Ferdinand Omanyala of Kenya lowering it to 9.77 seconds later that year.

East Africans are known more for their great exploits in long distance and endurance races due to the adaptation of their physiologies as a result of the high altitudes of their habitats, but Ferdinand is one of a kind in Sprints from that part of the continent, an athlete by accident, because his ability was spotted while playing his original sport Rugby and he was recommended to a coach who turned his destiny around.

Seeing that Simbine and Omanyala are still active, who knows if one of these two could eventually cement his name in the history books and deliver on the biggest stage?.

The story is not too different in the women’s category of the events.

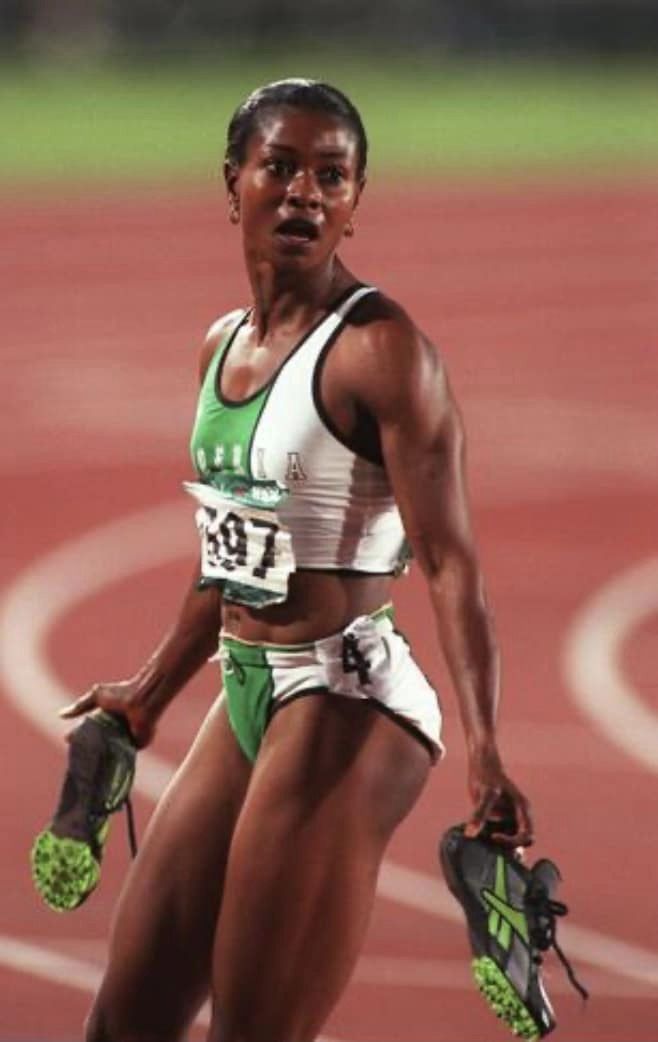

Christine Mboma of Namibia won a silver medal in the 200m at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics at a tender age of 18, becoming the first ever Namibian woman to win a women’s Olympic medal and breaking the world under-20 and African senior record thereby with 21.78 seconds effort, bettering Nigeria’s Mary Onyali’s earlier 22.07 seconds that was run at the Golden League in Zurich in 1996. Hence, Mboma’s effort remains the Africa’s highest honour in women’s sprints till date, also outdoing Onyali who won a bronze medal at the same event at the 1996 Olympics.

In the race of her life, the iconic Mary Onyali came third at an astonishing time of 22.38 seconds behind French Marie-José Pérec’s 22.12 seconds and Merlene Ottey’s 22.24 seconds at Atlanta 1996 Olympics to win a “golden” bronze medal for Nigeria, the first of its kind in the history of Africa in that category.

At the same 1996 Summer Olympics, Nigeria’s Falilat Ogunkoya won a bronze medal in the 400m, behind Marie-José Pérec of France and Cathy Freeman of Australia, in a personal best and African record of 49.10, which was the first sprint race’s medal for any African woman athlete ever. But the 400m event requires a bit of endurance, so it is outside the focus of this article.

Ivory Coast’s Marie-Josée Ta Lou impresively ran 10.86 seconds to finish fourth in the 100m final at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, missing out on a medal by seven-thousandths of a second (0.007). She then won silver medals in the 100m and 200m at the 2017 World Championships, the latter in the national record time of 22.08 seconds. Despite her 10.72 seconds 100m best making her the African record holder, she still fell short of the ultimate mark.

As the time ticks on towards the 19th World Championships this summer (August 19-27) in the Hungarian capital, Budapest, are we finally going to see another sprinter following in the footsteps of Namibia’s Fredericks by winning a gold medal while flying the flag of an African country?

Well, time will tell.

References:

- Genes for Elite Power and Sprint Performance: ACTN3 Leads the Way:

- Nir Eynon • Erik D. Hanson • Alejandro Lucia •

- Peter J. Houweling • Fleur Garton •

- Kathryn N. North • David J. Bishop, published 17, May 2013

- Druzhevskaya AM, Ahmetov II, Astratenkova IV, et al. Asso- ciation of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism with power athlete status in Russians. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;103(6):631–4.

- 3. Eynon N, Ruiz JR, Oliveira J, et al. Genes and elite athletes:

- Tonchi, Victor L., William A. Lindeke, and John J. Grotpeter, “Fredericks, Frankie (1967- )” Historical Dictionary of Namibia. 2nd edition.

- BBC Sport. 5 August 2012. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Tchechankov, Ivan (10 June 2011). 2011 already a record-breaking year for the men’s 100 metres – Updated. IAAF. Retrieved on 11 June 2011.

Please follow us on the YouTube by subscribing through this link: https://youtube.com/@moorsportz

(Edited by Abimbola Ajayi and Chris Adetayo).

With contributions from Enefiok Udo-Obong;